Dr. Diana Batchelor

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Oxford

Sometimes offenders don’t take full responsibility for the crimes they have committed. They may be unremorseful, unable to answer victims’ questions, or even entirely unwilling to participate in a restorative justice process – as is their right, given that participation is voluntary. However, our research shows that with the right information, preparation, and support, victims can still achieve at least some of their goals through a restorative justice (RJ) process. In collaboration with practitioners at Thames Valley Restorative Justice Service, we have written a new guide to help practitioners manage these types of challenging cases. We don’t have all the answers, but we provide a combination of practical tools and things to consider.

For many years, the guidance in England and Wales has been clear that restorative justice processes should not be used if the offender is denying the offence. The purpose of this ‘rule’ is to avoid using a justice mechanism with people who may in fact be innocent, and to avoid falsely raising expectations, or revictimising participants (Collins, 2016).

Like most things in life, the reality regarding ‘taking responsibility’ is more complicated than is often assumed. Offenders do not necessarily either wholly accept or simply deny responsibility for a crime. For example, they may admit that they took part but did not initiate the crime, that they carried out some parts of the crime but not others, that they didn’t intend to do it, that they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or that they don’t remember exactly what happened. These attitudes are so common that forensic psychology has a multitude of labels for them, including cognitive distortion, neutralisation, rationalisation and minimisation, among others (Kaptein and van Helvoort, 2019).

So, instead of simply considering a case to be either ‘suitable’ or ‘unsuitable’ for restorative justice, it can be useful to consider the offender’s position on several different scales. We found that offenders’ attitudes differed on a few different dimensions, including: willingness or ability to listen to the victim; admission of guilt; victim empathy and remorse; willingness or ability to offer information about the offence and answer questions; and willingness or ability to offer other specifics desired by the victim (e.g. reparation, compensation, returning stolen items, or attending rehabilitation programs). It is possible for offenders to be high on one scale and low on another.

Given this range of offender ‘cooperation’ within a restorative justice process, it can be difficult to inform and prepare victims for participation (the same can also be said for offender expectations of the victim, but this research focuses on victims’ goals). Experienced facilitators often already know how to balance the offender’s ‘offer’ with the needs of the victim, through careful preparation and shuttle mediation. Although navigating this difficult balancing act may come naturally to some, however, it is important to be able to describe it to participants, to other practitioners, and to new facilitators. We hope that this practitioner guide will make some of the issues and complexities involved in the balancing act more transparent, so that victims can make fully informed decisions and manage their own expectations. We believe there is always room to reflect and improve on practice, and we hope that this guide will help with that.

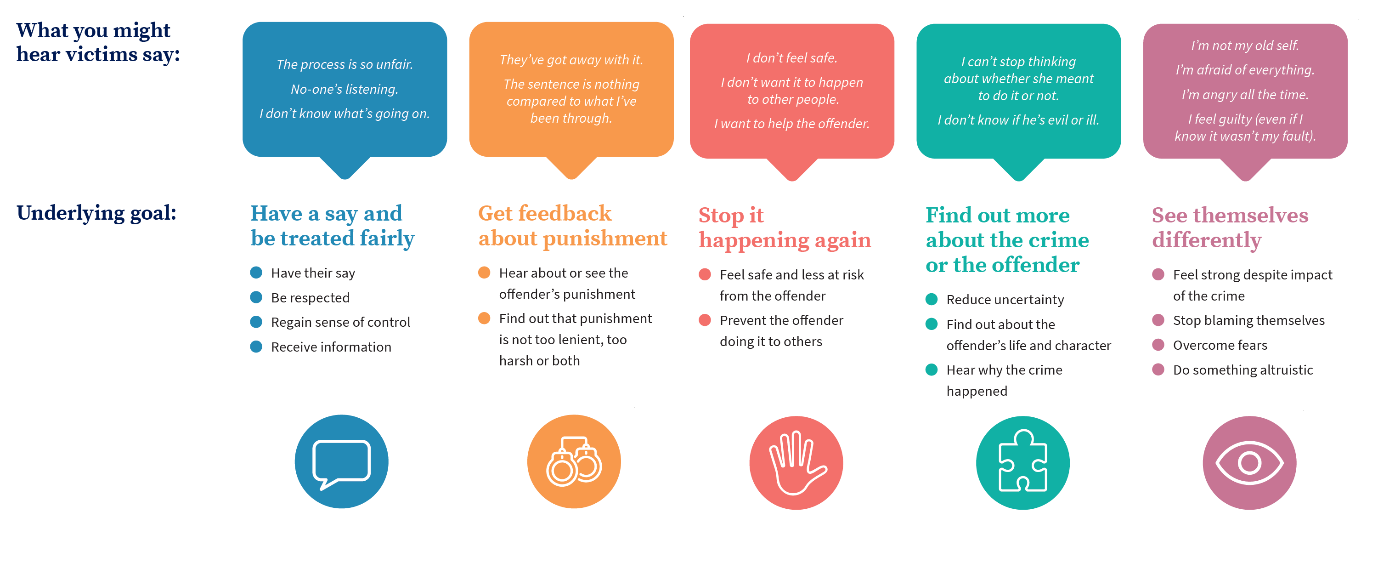

As part of the research, I interviewed 40 people affected by a range of offences, either before, after or both before and after a restorative justice process (Batchelor, 2019). The research was also informed by insights from clinical supervision meetings with restorative justice practitioners from Thames Valley Restorative Justice Service over a period of three years. We identified that victims tended to have five main types of goal for a restorative justice process. Of course, these categories do not cover every individual experience, but they arose repeatedly among the victims we interviewed for the research, and these goals seem to incorporate many of the other more ‘surface’ goals that victims mentioned.

In the guide, we discuss each goal in depth, and consider how they may be met with different levels of offender cooperation. When the offender is unable to provide everything the victim is looking for, it becomes even more important to help victims identify and understand their own underlying goals. For example, a victim could say that they want to meet the offender because they want their mother to hear from the offender. But is this because they want their mother to believe it happened, so that they feel less of a victim? Or is it because their mother will ask questions the victim feels unable to ask, so that will help them to find out about the offender? In this example, if it is not possible for that victim’s mother to meet the offender, there may be other ways of achieving their underlying goals – as long as we know what they are. If their main goal is to see themselves differently, a meeting between the victim and their mother may help. If their main goal is to find out more about the crime and the offender, shuttle mediation with the offender may help, even if the offender is unremorseful or unwilling to meet. Again, by identifying victims’ underlying goals, victims and facilitators can work together to find alternative ways of achieving them.

The guide is free to download for whoever wishes to use it. Wherever possible, we include practical suggestions for facilitating these challenging cases, but many of the issues raised in this booklet have no easy answers. We mostly hope, therefore, that this guide will stimulate further discussion, research and sharing of best practice. You can download the guide at www.dianabatchelor.com/challenging-cases.

Victims who are considering communicating with the offender may wish to read the accompanying booklet Difficult Conversations: What do victims and survivors say about taking part in restorative justice. This booklet draws directly on quotations from people who took part in restorative justice. Its purpose is to help victims identify their main goals and consider whether they can be fulfilled through communication with the offender.