In our third research summary, intern Karl McGrath has kindly reviewed the article by Goulding, Hall & Steels (2008), Restorative Prisons: Towards Radical Prison Reform (Current Issues in Criminal Justice. 20(2) 231-242). Building on the summaries of Hopkins (2015) and Clarke and Williams (2018), this article develops the concept of a restorative prison and considers the potential and the challenges of introducing restorative values in the prison environment.

Key Message:

“It is not enough to have a single project to demonstrate ‘look how restorative we are’ – rather a prison needs to look at all ways it can fulfil the values” (Liebmann, 2007, cited in Goulding, Hall & Steels, 2008).

Summary:

In this article, Goulding, Hall & Steels explore the notion of a wholly restorative and therapeutic prison as an alternative to existing prisons.

They begin by arguing that the use of imprisonment has been growing worldwide in recent decades despite high financial costs, as well as the limited, and at times counterproductive, effects of imprisonment. The authors argue that the prison environment tends to: encourage, rather than discourage, coercion, brutality and violence; replace prisoners pro-social networks with anti-social networks; and often fails to prepare people in custody for life in the community. What’s more, prisons are part of a broader criminal justice system that typically focuses on punishment rather than restoration, and crimes are usually seen as offences against the state rather than against the person or the community. Victims are poorly served and there is little incentive for offenders to accept responsibility for their actions. In this context, Goulding, Hall & Steels write that “in their present form, prisons have served their time and real reform is called for”.

For the authors, real reform means adapting and applying the basic principles of restorative justice to the prison setting, moving away from the brutalising and punitive characteristics of current prison regimes towards a more reparative and healing approach where victims and communities are active participants. To be clear, the authors are not talking about simply adding a restorative project or unit into a prison, but are advocating for prisons whose regimes are informed entirely by restorative and therapeutic principles. The authors acknowledge that this is a relatively new concept and, as such, there are very few real world examples in existence (with the exception of some prisons in Belgium) to demonstrate how such prisons would look and feel. Nevertheless, the research suggests that the potential benefits would include greater victim satisfaction with the criminal justice system and a reduction in offending of roughly 30% when combined with effective therapeutic interventions.

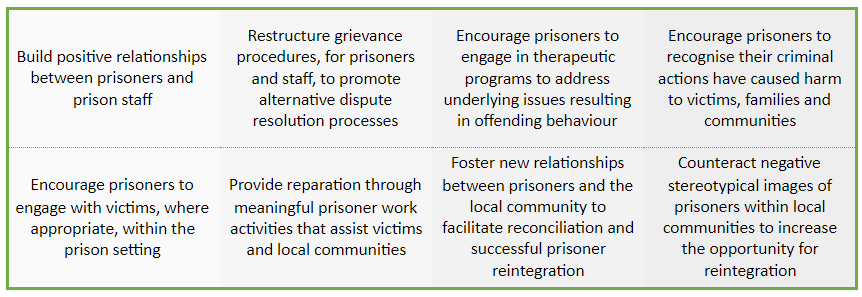

However, in order to work effectively within the prison setting, the authors suggest restorative justice should address these 8 areas of fundamental concern:

Figure 1: Areas of Concern for Restorative Justice Processes in Prisons

Belgium is one of the few places that can provide some guidance on the implementation of restorative and therapeutic prisons. In 2000, a restorative philosophy and practices were introduced to selected prisons to cultivate a prison culture that encouraged restorative processes between victims and offenders. Staff in the selected prisons underwent extensive training and education in the principles and practices of restorative practices. Prison officers were also required to develop generic therapeutic skills to facilitate restorative and therapeutic processes in diverse situations. Tensions between traditional ways of working and the more restorative-therapeutic approach persisted for some time, though the employment of consultants in each prison to raise awareness of restorative processes and establish meaningful dialogue between prisons and their local community is said to have eased the transition. Victim-awareness and reparation programs were set up to support prisoners throughout their sentence to accept responsibility for the harm their offences while providing reparation for victims. Finally, implementation efforts inside selected prisons were supported in the early stages by an intensive program of community information, which helped to prepare both victims and communities for the radical change toward a restorative approach.